Management

It takes as much work to build great teams as it does to build or become a great leader.

I believe that if you were to ask my family (wife and two daughters) they would tell you that I’m the most patient man in the world…. until I’m not! I seem to have a great deal of patience for most situations but when I run out of patience I don’t come down gradually. Nor do I stair step down one level at a time. My patience ends like a rock being kicked off a 1,000 foot cliff that plummets with the acceleration of gravity until it smashes on the floor of the canyon. My girls actually developed into an early warning system for me. When I would see them quickly jump up and bolt from the room in unison, I began to understand that my patience was approaching the cliff and they had picked up the warning signs.

One of my clients currently has a similar trait. He has a great deal of desire and compassion to grow and develop his team and constantly pushes them to become better then they were the year before. He will start a project that is going to challenge and grow them over time and then gives them enough time to accomplish the task. But, if he is not seeing sufficient progress as critical deadlines approach, his rock will eventually get kicked over the cliff and then he jumps in with great fury and gets the task completed.

Why do we reach this cliff where things go bad in a hurry? A couple of reasons are very obvious to me.

1. Leaders mistakenly assume that members of their team will “see it” (understand all that needs to be figured out in order for the growth spurt to take place) or will figure it out along the way in their effort to complete the task or project

2. A basic misunderstanding of good project management

By definition, a growth experience can’t necessarily be figured out ahead of time. It’s a new experience. You’re figuring out something that you’ve never seen or experienced before. You’ll either not see it at all or if you do you may not execute in a very efficient or effective manner. Leaders often forget their own learning curve experiences. They made these same mistakes years ago or even if it was only recently that they figured it out, they now only remember the end state of the new knowledge, not what they went through to learn the new behavior or understanding.

Leaders must work harder then they expect to help people understand the new expectations, learn the processes it will take to get there, and have a vision of the new normal. Develop patience for the sake of your teams.

Why are so many feeling that our Work-Life Balance is out of whack? In this series, I will explore four categories of issues that contribute to the feeling (and actuality):

Several years ago I learned some very interesting lessons about time management. I was working with a high level leadership team, all vice-presidents and above. While we were offsite spending time on leadership development issues one of the VP’s on the team finally stopped the process and said something like the following:

“Ron, we think all of these leadership issues you’re trying to teach us are wonderful and important, but until you help us with our time management problems, we can’t even think about putting more effort into improving our leadership skills. We’re all working at least 60 hours a week as it is. We’re destroying our health and our families. Help us with our time management first and then we’ll be ready to learn new leadership skills from you.”

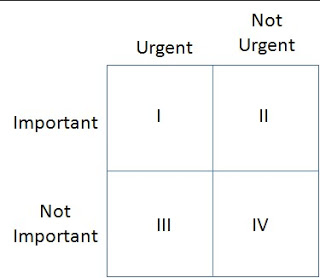

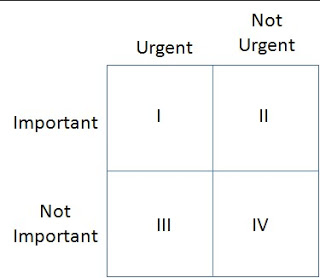

He was right. They were worn out and suffering. I turned to a time management model put forth by Steven Covey in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. In that book, Mr. Covey indicated that all of our time fits into quadrants of a two-by-two grid.

His premise was that once we fulfill all of the tasks in Quadrant I (both urgent and important) we tend to go on to tasks that fall primarily in Quadrant III (Urgent but not necessarily important).

I sent the team off to record where all of their time went over the next two weeks. When they returned with the record of approximately 120 hours each had expended over the last two weeks, we listed every activity for each participant on a flip chart and posted it on the wall. Then we went through a very interesting exercise. Line-item by line-item we went through each chart and identified into which quadrant it should be placed. A very interesting pattern began to emerge. On several of the line-items, the owner of the sheet would say that he/she had spend a number of hours producing a particular report (as an example) that was urgent but not important and they intended to stop performing that task in the future. However, once stated, there always seemed to be a challenge from the room. Someone would say, “If you don’t produce that report, I can’t get my job done. It must be placed in the important row.”

But, when we began to look into what data in the report was required, there often seemed to be a simple solution to the second persons needs that still eliminated the effort needed to produce the report (it’s on the web site, a quick email, it can be found in another location, etc.) The problem was solved and the bulk of the work eliminated.

Once we completed all of the “negotiations” around the room and everyone had agreed on the quadrants into which all work had been placed, a horrifying statistic emerged. Only 20% of all the work fell into the “Important” row. One VP hung his head and said:

“Do you mean to tell me that I just spend 24 hours of meaningful work over the last two weeks and all the rest was just thrashing?”

I’m afraid so.

The lessons that I have learned from this experience (conducted now several times) include:

- It’s difficult (impossible) to determine on your own how much of your work falls into which quadrants. There is always someone else that needs to be brought into the negotiations.

- It takes team support to stick with the decisions. Even after everyone agrees that you have some quadrant III work that can be dropped, there will be those who still want you to do it. It takes a team to help you say “no”.

- If more than 70% of your work falls into quadrant I (both urgent and important), you’re headed for burn out and failure somewhere down the line because you are not doing enough important but not urgent work (prevention, production capability, relationship building, big picture thinking, etc.)

The links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the FTC’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Building trust is an essential part of leadership, but people aren’t likely to trust you if they feel they don’t know you at all. That was the problem with a manager I was asked to help.

Her biggest issue is that she didn’t let people in. She was a leader – people reported to her – but her people didn’t feel like they understood who she was. She seemed very distant and aloof.

And it was intentional. When I spoke with her about it, she said:

“I don’t want to have people from work in my personal life. I don’t want them knowing what I do, or what sort of person I am.”

Her problem wasn’t arrogance or disdain. She felt vulnerable. She was trying to protect herself.

My challenge was to show her there was a way to connect with her people that didn’t involve the sort of intimacy she feared. I spent our first-day session together modeling how to do this. When we got to the end of the session, I asked, “How well do you think you know me now?”

She replied, “I know a phenomenal amount about you.”

“Really?” I said. “How is that?”

“Every time I asked you a question, you told me a story that related to that topic.”

I told her I did that deliberately because people remember stories, and they also connect with the person telling the story. She was feeling like she knew me almost intimately after just one day, and all because I told her six to eight stories as we were talking.

“You can do the same thing,” I said. “You don’t have to bare your soul with people. You just need to start telling stories about the things you’ve done and how you’ve learned what you know.”

It was a very powerful lesson for her. She walked out of the session thinking, “I can do that. I can tell stories.” I think it made a huge difference in her leadership ability.

Ron’s Short Review: Our economy is based on much more than the old supply and demand understanding. This is about being relevant in today’s economy.

Ron’s Short Review: Our economy is based on much more than the old supply and demand understanding. This is about being relevant in today’s economy.

Ron’s Short Review: How our brain actually works and how that impacts our image of management and leadership.

Ron’s Short Review: How our brain actually works and how that impacts our image of management and leadership.

Ron’s Short Review: Making the shift from being a manager to being a leader takes different skills.

Ron’s Short Review: Making the shift from being a manager to being a leader takes different skills.

Ron’s Short Review: Ancient principles never get old.

Ron’s Short Review: Ancient principles never get old.

Ron’s Short Review: Bossidy was a good manager. Today when I see him on CNBC he seems to have great principles.

Ron’s Short Review: Bossidy was a good manager. Today when I see him on CNBC he seems to have great principles.

Ron’s Short Review: Pretty well researched ideas.

Ron’s Short Review: Pretty well researched ideas.

Ron’s Short Review: GE had an incredible run under Welch even though he’s backed away from some of the principles in recent years.

Ron’s Short Review: GE had an incredible run under Welch even though he’s backed away from some of the principles in recent years.

Ron’s Short Review: More about management and execution than leadership but a good book none the less.

Ron’s Short Review: More about management and execution than leadership but a good book none the less.

Ron’s Short Review: One of the first to distinguish the difference between leadership and management.

Ron’s Short Review: One of the first to distinguish the difference between leadership and management.